HackUMASS 2023

So me and four of my friends won Best Software and Best Security at our school's hackathon. We didn't finish what we sought to set out, but we ended up with honestly a pretty seriously cool project that's like one more hackathon day away from being fully featured.

initial idea

Our group was just four of us at first, Steven Jun and Max, and our initial idea was Steven's: to have a showcase of a bunch of operating systems (windows 32, early versions of linux, whatever) in the browser, almost like a museum. We kinda shot it down though, because while fesible, we would either have to do screen sharing for a bunch of really old operating systems, which sounds like an impossible task, or basically just be doing a bunch of vm configuration, which sounds kinda boring and also maybe not fesible, especially considering the thing we might end up having hosted it on would just be Jun's PC.

Me and Max are sitting in our dorm thinking about it, and we're trying to figure out a way to make either fesible or less annoying. I don't remember who thought it up, but eventually we were like "what if we emulated an old operating system" which eventually led to "what if we emulated Linux in the browser?" I said there and then if we could get linux running we would have a guarenteed win, and he agreed (spoiler we did win things, we did not get linux working).

This new idea actually solved both our problems. It's not annoying becuase there's no having to deal with qemu or something and actually we can just make the client's computer do all the work. It's fun because both of us actually enjoy lower-level programming and this is about as fun as a project could get for us. This is about when I called Marshall like "hey wanna do the hackathon" and he's like "not really" and then I'm like "but our project is running linux in the browser" at which point we start getting into a conversation about the logistics of it, and after a couple minutes he's just like "okay well I'm clearly interested in it so I guess I'll do it" and thus completed our five man team.

Since all three of us were already locked in and Jun and Steven didn't have any other ideas in particular, they were convinced and as of then a couple days before the Hackathon started we had finalized our idea: Run Linux in the browser. Practically, as I understood it then, it would just mean simulating a CPU and RAM. Everything else would be done by the operating system that we ran said CPU, which would be Linux. As for simulating the CPU itself, we definitely weren't going to do an intel x86-64 with it's 3,684 instructions, and while ARM was much better, RISC-V was a clear winner given that we only had to implement 77 instructions in the end.

From that point, Max and I both found videos of people implmeneting tiny linux emulators in various languages and vowed to watch as much of them as we humanly could until the Hackathon started. I think I probably spent 8 hours watching RISC-V emulation videos at double speed, but honestly had me and Max not done that we probably wouldn't have finished.

hackathon starts

and we have to start divying out jobs. Our plan is to go light on the sleep deprivation the first day and then absolutely kill ourselves the second day. Some things will be pretty easy to delegate, some things will be more difficult. All I knew for sure there was I would have Me, Steven and Jun working on disassembling and decoding instructions, while I'd have Marshall and Max doing the weirder hardware-esque stuff that we were more unsure about. My job more than anything else was kinda organizing the code structure of the bits I was working on.

For decoding, what we'd do was we'd go back and forth between the RISC-V documentation and our code and just implement each group of instructions manually. This wasn't too difficult, it was basically just a bunch of nested switch statements and bitwise arithmatic to parse out each different field. Some of the more fun instructions had different bits of the immediate scattered around the immediate and we had to basically unscramble it before we could put it into assembly.

Our decoding code ended up looking like this: we'd parse out the opcode, get the type from said opcode (there wasn't any rhyme or reason as to which opcode corresponded to which instruction, so Jun and I just went through the entire documentation matching each opcode to each type) and then continue to parse values from that point on. It ended up looking like this:

export function decode(op, i) {

const opcode = op & 0b1111111;

const type = gettype(opcode)

switch (type) {

// U was the shortest type

// the reason it's in a new block is because switch statements don't actually

// create new blocks, so we couldn't have two constatns named `imm`, even though

// basically every single type is gonna have at least one operation that takes an

// immedaite

case TYPES.U:

{

const rd = bitsfrom(op, 7, 5)

const imm = op & (~0xfff)

switch (opcode) {

case 0b0110111: i.LUI(rd, imm); break

case 0b0010111: i.AUIPC(rd, imm); break

default:

throw new Error(`Illegal opcode for instruction ${op.toString(16)}`)

}

}

break;

}

}

As the first day came to a close, we started approaching a working disassembler (and Max and Marshall had RAM read/writes working) and I was thinking about testing. We absolutely needed testing, one because it looked cool to have a bunch of passing tests, two because it would look good to judges, and three because there wasn't a chance in hell we'd be able to easily debug assembly. The question was, how can we test decoded instructions?

decoding / testing

When you decode the instruction, it will call the appropriate assembly instruction with the appropriate registers and immediates. We had two options here

Execute the instructions immediately after decoding. This would mean to test we'd have to test an instruction we'd actually have to construct a full hex assembly instruction like what you'd see in the binary and that sounds really annoying so we didn't do that

Execute some function with the parameters we parse out. This would mean we'd be able to test the function alone and pass whatever registers and immediates we wanted into it. This is what I initially settled on. The import statement would be really, really long but hey what can we do.

As I was going to sleep the first night, however, I didn't really like it. We were on the cusp of having a usable product, a disassembler, but it would just be calling the functions so unless we modified every single function to print out the disassembled instruction, it'd only really be able to execute. Then I realized, instead of modifying every function, we couold just execute different instructions entirely.

Specifically, instead of importing a bunch of different functions, pass in a huge dictionary of functions that can do whatever we want them to do. In addition to making a dissassembly instruction set really easy, it would also make debugging our disassembly a lot less of a pain.

our tests ended up looking like this for decoding, where the second parameter for decode is our instruction dictionary. Had we not done this we'd have to manually check registers before and after, and at this point in the project we literally did not have registers, so it was kinda a necessary innovation.

//actual code is way worse formatted but hey it was a hackathon project

import { decode } from "./decode.js"

import {test, expect} from "bun:test"

const wantparams = (val) => (...a) => expect(a).toEqual(val)

test.skip("decode j suite", () => { decode(0x6f000000, { JAL: wantparams([0, 0x0>>0]) }) })

test.skip("decode r suite", () => { decode(0x33058500, { ADD: wantparams([10, 10, 8]) }) })

test.skip("decode i suite", () => { decode(0x8320c100, { LW: wantparams([1, 2, 12]) }) })

test.skip("decode s suite", () => { decode(0x23261100, { SW: wantparams([2, 1, 12]) }) })

test.skip("decode u suite", () => { decode(0xb7170100, { LUI: wantparams([15, 69632]) }) })

//we didn't test the b suite :) thats fine tho nothing broke I think

execution

After this point we did actually have a full web disassembler so if nothing else we had something we could submit to the hackathon, but we were still dreaming of linux. We starte the next day early-ish, with Jun, Steven and I on execution, and Marshall on Max still on weird hardware stuff. We made our registers just a Uint32Array (actually everything was a Uint32Array because we can't use JavaScript's ambiguous "number" type)

Being able to get and set registers was really all we needed to start writing basic instructions, though, at least the math instructions. We'd later need CSRs and ram read/writes, but one of the most important things in a hackathon is having everyone working at all times so we kinda just started anyways.

Instructions were mostly easy, it was just a large dictionary of functions as I talked about before and a lot of them just operated on registers, but it wasn't all sunshine and roses. JavaScript numbers had come back to haunt us, specifically in multiplication. Until you hit 32 bits, JavaScript numbers are represented with just 32 bits. Past that I'm not exactly sure what it does, and actually I'm still not sure because I don't remember what issues we were having and I can't trivially reproduce them, but suffice it to say that from that point onwards we did everything with BigInts.

They were pretty simple, here are a couple simple/not so simple examples

const instructions = {

ADDI: function (rd, rs1, imm) {

setreg(rd, getreg(rs1) + imm)

},

MULHSU: function (rd, rs1, rs2) {

setreg(rd, Number(BigInt(getreg(rs1) | 0) * BigInt(getreg(rs2)) >> BigInt(32)))

},

JALR: function (rd, rs1, imm) {

setreg(rd, getpc() + 4)

setpc(((getreg(rs1) + imm) & ~1) - 4)

}

}

Then to actually run the program, we simply load the entire assembly into ram, do some ELF parsing to initialize registers/pc/whatever, then basically just loop these three functions forever until it terminates.

const op = read32(getpc())

decode(op, instructions)

setpc(getpc() + 4)

everything else I did

That was most of the lower-level code that I worked on. Max and Marshall did CSRs, memory, and started working on traps I think? Jun and Steven worked with me. I also did the actual website that we'd be using to host the service--I wanted to do it using google cloud because the last hackthon we did we wanted to win the google cloud backpacks but we didn't finish our project so I didn't put it into that category. No one else did either though, so if I just did we all would have had google cloud backpacks by now so this time I was determined to use google cloud even if it did basically nothing for me.

So I just did the server hosting stuff. I tried using firebase but it was annoying, I actually tried a whole lot of different things but eventually I settled on using some service that basically would just run a simple express app. Eventually the website just had a simple file upload to upload your binary, it would decode the binary and print out the instructions and it would eventually print out any output from the program, but CSRs had to come first.

back to the second day

It was nearing the end of the second day. Some time I think between 11:00 and 2:00 did Steven and Jun go to bed, with Marshall soon following. Eventually it was just me trying to host the website on google cloud (I had never used google cloud before) and Max trying to get CSRs and ELFs working so we could print things and not have to start from pc=0 respectively. Eventually I did get hosting working at between 2:00 and 4:00 and I left to sleep as well. Max, the absolute legend, stayed there all night. When I woke up and came back to where we were working, it was like a dream come true--both ELFs and output were working, though we were haivng some issues with jumps and I had to implement file upload and the decoder on the website.

With about two minutes to spare we completed it, and while we still didn't have traps or like half the CSRs, which were necessary to get linux running, we could run semi-complex assembly and we could actually run C code that we compiled for RISC-v with GCC. It was more than I could ask for and honestly Max is definitely the MVP of the project for doing both CSRs and ELFs by pulling an all-nighter.

judging

Our project wasn't particularly showy. It was a basic website that outputted plain text when we put some binary file into it. We had to exclusively rely on the judge's techincal knowledge in order to understand how cool of a project it was for us. I still don't know exactly how well we placed in the judging, but we know we didn't straight out get top 8 because the top 8 were awarded with like a Wolfram Mathematica code or something, so presumably the judges weren't particularly impressed. Ben Burns, however, one of the organizers (and also sorta my boss as a UCA) thought that one of the judges who didn't actually ever end up judging our project specifically would really like it and thoguht it would be cool to just show it to him anyways--Tim Richards. He tought the intro to C and OS classes so Ben thoguht he'd get a kick out of our project.

And get a kick he did. He really liked it. It was really nice to see someone so enthusiastic about it after one of the judges being a data scientist who didn't know anything low level and a couple judges who seemed pretty unenthusiastic. He was like "this must have been so hard" and we were like "you get us :D". Anyways I can only image the reason we ended up winning best software is because either he or another one of the organizers put in a good word for us, since our project really was very technically intensive, but just wasn't really showy enough to score well in the hackathon otherwise.

That being said I heard from an organizer later that we almost didn't get anything at all becuase we didn't actually link the GitHub page on our submission--they only got it because one of the organizers was following Max on GitHub and could somehow get to Steven's page who hosted it to look at the code--apparently it wasn't actually called HackUMass either.

So we won best software hack, which is pretty cool since out of literally all the software projects there, we won. As for best security hack, we were the only person in the category lol

awards ceremony

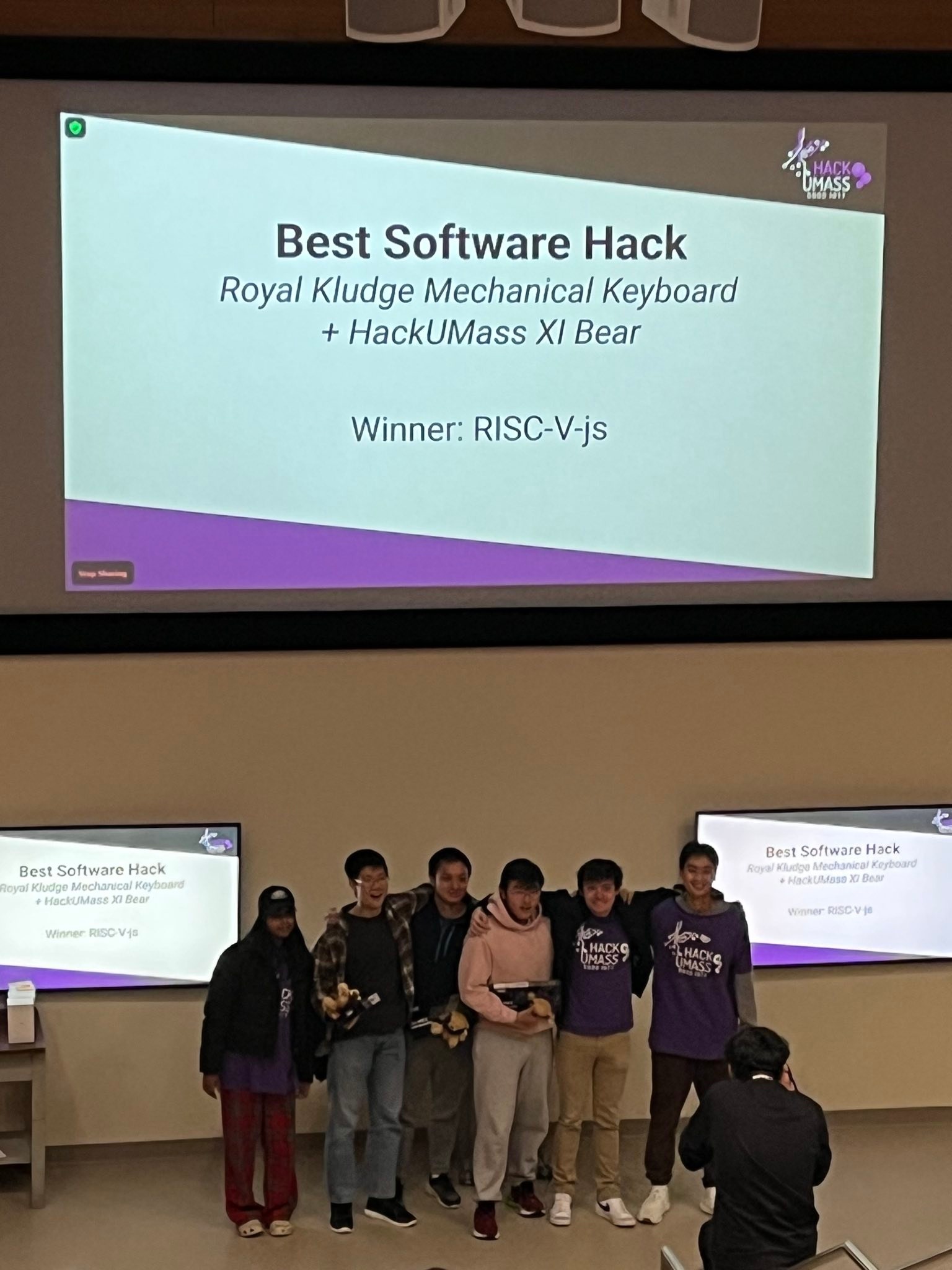

yeah I was asleep the entire time lol I was completely passed out for like three hours and then when I woke up I had a ton of messages and missed calls. There's a really good picture of Jun, Steven, Isaac, Max and some other organizers or something? recieving our awards which is especially funny given that had I been there all my roommates would be in that picture (me, Steven, Isaac and Jun live together) but I was completely out.

On the left we have my team claiming their prizes and three orgnizers, one of whom being my roommate, and then we have me at the same time:

We did only get four prizes though due to the nature of the competition, so Marshall didn't end up getting anything except for the w keycap from the mechanical keyboard that I won, which I traded with his, which we exchanged during a 240 midterm that I ended up getting a 65 on.

It was really fun, idk if I'm ever going to do it again now that I won a pretty big award. If I put the new one on my resume then I'd probably have to cut the old one (or cut something else) and also like I feel like the intersection between fun project and projects that win hackathons is pretty small but maybe I'll do it

also Eric was at our table the entire time he wasn't on our team he was doing his own thing but maybe he was our team mascot or something. We love Eric. How is this the last sentance in this entire blog.